A Book Through Time

- Lucy Vinten

- Sep 27, 2020

- 6 min read

Book provenance is an area of research into the history of individual books and of libraries, focusing on who owned which books, and what other books they kept in their libraries. Knowing the contents of a persons or institution’s library gives an insight into the study of their life and thinking. It allows us to see what people in former ages were interested in (even if they did not read the books, they must have been interested enough to buy or to keep them) and how they formed their ideas. Book provenance can show us how readers in former ages interacted with their books. This blog post looks at one book in the Jesuit Antiquarian Book Collection, and shows how close study of the inscriptions and other marks of ownership in it reveals much about the people and institutions who have owned it.

Cover and title page of St Teresa of Avila’s autobiography ‘The Flaming Hart or the Life of the Glorious S. Teresa’, 1642 (ref. ALBSI/A/245)

The book is St Teresa of Avila’s autobiography ‘The Flaming Hart or the Life of the Glorious S. Teresa’ published in 1642. It is in English, translated from Spanish by Sir Tobie Matthew, the son of an Anglican Archbishop of York who later converted to Catholicism, became a priest and had a close association with the Jesuits. It was printed in Antwerp by Iohannes Meursium, who published other works of interest to English Catholics. Due to the danger of publishing Catholic works in England, many were printed abroad then smuggled into England, a fact which Tobie Matthew alludes in a note to the Reader at the beginning where he apologises for any errors and blames the printers who do not speak or read English ‘… to excuse the few faults which shall be found, in the Print; the rather, because it was performed, both in a strange countrie, and by strangers.’

The book is smallish, with a plain vellum binding. It used to have leather ties to keep it closed, but these have broken off, and a very basic repair has been done on the spine using sticky tape, probably at some point in the late 19th or early 20th century. It fits very well into the Jesuit Antiquarian Library, both in terms of subject matter, and in its physical characteristics. It is not elaborately bound and has spent much of its life as part of a working library. It has clearly been well used, and the fact it has been repaired shows that it has been valued. All the pages of the text are present, but it lacks a frontispiece which we know used to be present because there is another copy of this book in Lambeth Palace Library which still has its frontispiece.

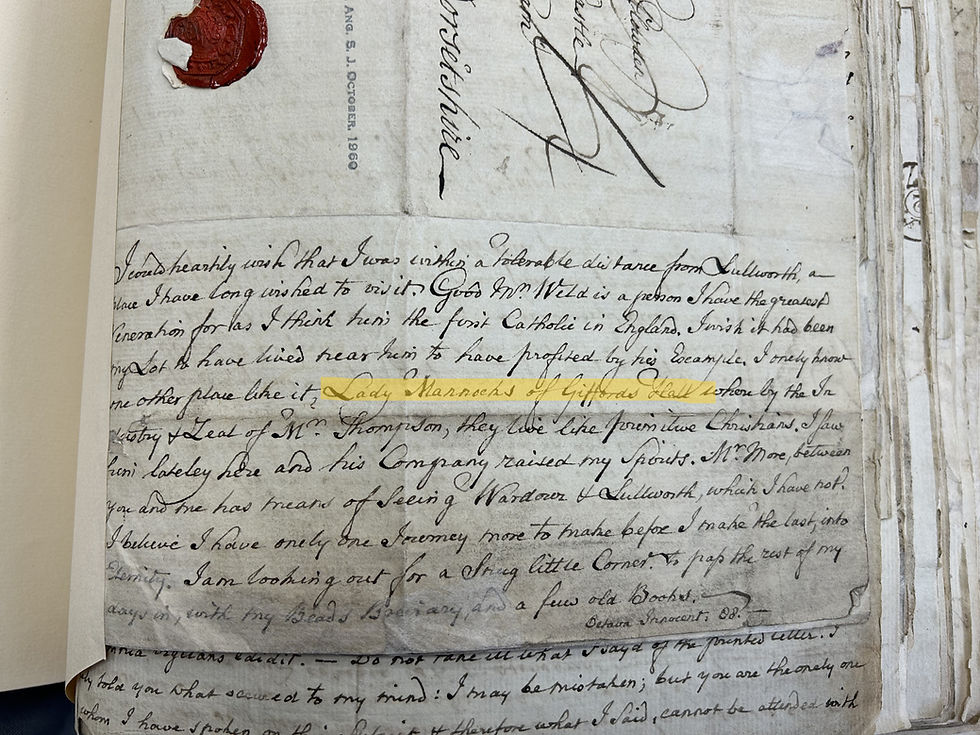

Unlike many of the books in the Jesuit Antiquarian Book Collection, this one does not have many annotations in its text, although someone in the late 19th century made some notes on little slips of paper and inserted them in a few places throughout the book. It does have several inscriptions at the beginning, as well as bookplates, which are unusually informative about the provenance of the book.

The earliest inscription in this book reads ‘E Libris Jo: Warner de Parham, Com Suffolcia’. Pre 6s-8d’ ‘From the library of John Warner of Parham in the county of Suffolk. Price 6 shillings and 8 pence.’

John Warner of Parham was a gentleman who in 1659 married Trevor Hanmer, daughter of Sir Thomas Hanmer, and became a baronet in 1660. In 1664 John and Trevor converted to Catholicism, and they agreed to separate. Both joined religious orders. Trevor joined the English nuns called the Sepulchrines at Liège as Sister Claire of Jesus in 1665. John joined the Jesuits, later becoming Confessor and Consultor at Watten, close to St Omer. The convent of the Sepulchrine nuns had been founded in 1642 in Liège, a location chosen partly because of its proximity to the English Jesuit College, and there were close links between the two institutions. There are no extant pictures of John, but a portrait of Trevor is in the National Portrait Gallery.

Given that John Warner became a baronet in 1660 and the inscription does not call him ‘Sir’, we can assume that he bought the book before 1660. The book was published in 1642, so it was still relatively new then. Warner’s ownership of St Teresa’s ‘Flaming Hart’ suggests that he was reading Catholic spiritual texts in the years before he converted to Catholicism, and presumably that his wife, Trevor, was as well.

Although the book has ended up in the Jesuit Library in Mount Street, London, it seems that John Warner did not take this book with him when he became a Jesuit, but instead that his former wife Trevor took it with her to the convent at Liège in 1665. Inside the front cover is another inscription, stating that the book has been catalogued by the nuns: ‘Written in the Catalogue of the Inglish Religieus of the holy Sepulchre at Liege’, and underneath is a shelfmark (H.9), indicating which shelf in their library the book was kept, and then the date 1789.

So for about 124 years, the book was in the Library of the Holy Sepulchre at Liège. At some point during this era another inscription was made: ‘Sister M. Ignatia with leave pray for me, A. Roper’

The Ropers were an English recusant family, and at least one Roper (Dame Mary) became a nun in the English Benedictine community in Ghent in the 17th century, but I have not been able to trace A. Roper or Sister M. Ignatia.

The Canonesses at Liège had to leave their convent in a hurry in 1794 because of the turmoil of the French Revolution, and after a long journey settled at New Hall in Essex. They brought their library with them, and much of it is now in the care of the Palace Green Library at Durham University, where cataloguing started last year. For a recent update on the cataloguing project, see one of their recent blogposts.

When their cataloguing is further advanced, it will be interesting to see how our volume from the Jesuit Antiquarian Book Collection fits with the other books from the Canonesses’ library, and how the shelfmarks match up with others in the collection, which will hopefully give us an insight into how the Canonesses organised their knowledge.

It is not clear when our copy of The Flaming Hart became detached from the rest of the Canonesses’ library, or when it arrived in the custody of the Jesuits, but we can be sure it was in the Jesuit library by the 1840s. We know this because there are four bookplates pasted in it from successive Jesuit library institutions based in Mayfair in London. The bookplates physically overlap each other, with earlier ones slightly on top of later ones. This could be confusing but is explained by the bookplates having been detached from the book and then re-stuck onto a folded sheet which has been inserted at the front at some point in the 20th century.

The oldest bookplate is from the College of St Ignatius at 9 Hill Street, Berkeley Square and dates from the second half of the 1840s. The Jesuits bought 9 Hill Street in late 1845 and lived there until 1850. The Jesuits then moved to 111 Mount Street, where they stayed until 1886, so the second bookplate in this book must date from between 1850 and 1886. This bookplate has been amended because the last ‘1’ of 111 has been crossed out and ‘4’ written in. This must have happened after late 1887, when the Jesuits and their library moved into the new buildings at 114 Mount Street -- but presumably before the new bookplates for 114 Mount Street had been ordered and delivered. When they were available, one was stuck in the book. The fourth and final bookplate ‘Ex Archivo Prov. Angl. SJ’ [From the Archive of the English Province SJ] is from the 20th century and marks the point at which the book was taken out of the library for regular use and moved to the archive, where the book still resides.

The close examination of just one book has shown its physical journey from where it was printed in Antwerp, to being part of a library of a rural English baronet who converted to Catholicism, then being taken by his former wife to her new convent in Liège, then back again to England in the aftermath of the French Revolution. Its movements over the last 170 years through various Jesuit libraries in different locations in London have been revealed. Further study, of the library shelf marks for instance, would no doubt reveal even more about the changing patterns of thought and use about St Teresa’s autobiography.

The Jesuit Antiquarian Book Collection is currently being catalogued, and future blogposts will share more discoveries made during the cataloguing process. In the meantime, if you are interested in the Antiquarian Book Collection or the Jesuits in Britain Archives, please do not hesitate to contact us: archives@jesuit.org.uk

Comments